Add 3 products to the cart and get the cheapest for free at checkout.

The Formula For Hard Hip Hop/Trap Drums

This guest post is written by Jelie, a Denver-based producer, rapper and business owner of Kickback Couture. In a series of articles, Jelie will be sharing her production tips with the BABY Audio community.

The formula for hard drums

Throughout the growth of Hip-Hop and numerous other electronic based genres, drums have gotten louder. In fact, drum loudness can easily make or break a production. With that in mind, I’ve shared some of my favorite tips for making my drums hit hard.

#1 Soft clipping

It would be easy if you could just dial-up the fader of your drum buss to infinity, but it’s not as simple as that. The problem many producers encounter when doing so is the same problem speakers encounter: This problem is hard clipping. Hard clipping is the audible digital distortion that occurs when a signal is pushed beyond its maximum/physical limit. This results in a harsh digital distortion.

Using soft clipping for harder results

Soft clipping is the answer for pushing your drums beyond the invisible ceiling. Rather than abruptly squaring off the signal, soft clipping is a gentle approach that rounds off the transients in a natural way to create a pleasing distortion effect that gets more extreme the louder you go. Examples of soft clipping effects are tube and tape saturators.

Soft clipping is achieved by using a non-linear cutoff curve on the audio waveform, similar to that in analog gear. A saturation plugin can achieve this effect and will allow you to crank up the signal in a natural sounding way. Play around with it until you have just enough loudness and hear the difference in your mix.

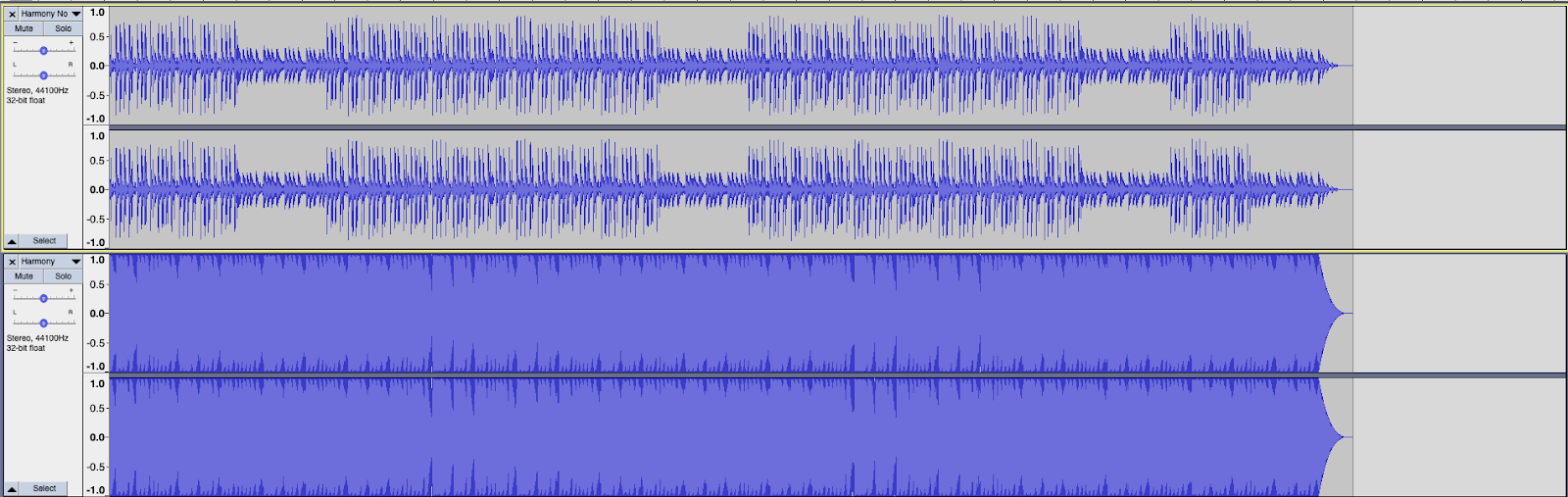

Below are two examples showcasing the effect that can be achieved through soft clipping.

#2 Parallel processing

Now that we’ve talked about the benefits of soft clipping, let’s move on to another classic formula for hard Hip-Hop / Trap drums. Parallel processing is when you make a copy of a signal and apply effects to that copy, typically compression or distortion. Once the effects are dialed in to taste, that affected signal is then blended with the original dry signal to combine the best from both. Parallel processing is a more subtle effect than applying the effects directly to the original track and allows for more flexibility. A couple tools that can be used for this type of processing are BABY Audio’s Parallel Aggressor and I Heart NY. You can hear some audio examples of those plugins in action below.

#3 using EQ to carve out space for the drums

This next tip is the most basic, but sometimes also the most effective. By applying EQ to each element in a production that surrounds the drums, you can create more space for the drums to hit harder. This gives the drums more clarity and perceived volume. For example, you can achieve this effect by adding a high pass filter to tracks in your production that don’t need low frequencies. Set the filters to taste and hear how it opens up space for your kick to punch through.

#4 Avoiding kick and 808 clashes

In Hip-Hop/Trap music, there’s usually some sort of bass present. This could be a real bass instrument, a sampled bass from Kontakt, or a synth bass. Most commonly in Trap, a synth bass will be present in the form of an 808.

The Trap 808 (a kick drum in its own right) can cause problems with your main kick as they both inhabit the same frequency area. There are a handful of ways to combat this problem and make space for both. Most notably, these methods are sidechain compression, complimentary EQ, sidechain EQ, altering the ADSR settings or any combination of the four. Let’s investigate them all!

Sidechain compression

Simply put, sidechain compression is when the volume of one instrument is controlled by another. In this case, the volume of the bass would be controlled by the volume of the kick, meaning that the presence of the kick lowers the volume of the bass. This can be setup with a compressor on the 808 track running with a sidechain input from the kick — or with any dedicated sidechain plugin. Listen to some examples of sidechain compression below.

Complimentary EQ

Complimentary EQ is when a particular frequency of one instrument is cut while another is boosted in the same area. For instance, we might cut the 808 at 60Hz and boost the kick at 60Hz. In addition, we may also apply a high pass filter to the kick at about 30Hz to leave space for the 808 to be present in this area. Listen to the audio clips below for examples.

Sidechain EQ

Sidechain EQ is similar to complimentary EQ, except it is based on the same processing concept as sidechain compression (i.e. only applying the effect when both instruments are present at the same time). Rather than setting a constant EQ, we can use sidechaining to ensure that the EQ will only attenuate when the kick and 808 compete for space. Some examples of this process below.

ADSR settings

Lastly on the list is altering the ADSR/envelope settings of the kick and 808. ADSR is an acronym for Attack, Decay, Sustain and Release, controllable in almost all synths. The Attack parameter is responsible for controlling the amplitude of the initial transient of a signal. A transient is a spike in volume, often the loudest part of a sound. For example if we raise an attack fader, we will hear less of the transient. A way we could use ADSR to help the kick and 808 gel together could be to invert their ADSR settings to ensure they peak at different times. Example: by shaving away the attack on the 808, we can leave room for the attack of the kick, and by shaving away sustain of the kick we can leave room for the 808 in between the transient hits. Listen to some examples of that below.

Bonus trick

A simple bonus trick used for making sure a kick and 808 have their own space to operate in is slightly delaying the 808. In other words, we would be applying a small amount of swing to the 808 by sliding its midi information to the right of the DAW’s grid lines — or leaving dead space at the beginning of a sample. Listen to examples of that below.

In conclusion

These were four main focus areas to work with when aiming for harder drums in your productions. On their own, each of them may seem subtle but in combination, they’ll do a lot to help your drums appear louder. After exploring some of these techniques, you’ll develop a list of favorite go to approaches to get the sound you’re looking for. Every producer does something different, which plays a part in differentiating each producer's sonic identity. So with that being said, don’t be afraid to experiment, and don’t hesitate to do things YOUR way. Simply said, do what works for you! We can’t wait to hear your mixes.

Go to all articles.

Learn more about BABY Audio and our plugins here.

.png)